Social Support Groups for Postnatal Depression Systematic Review

- Inquiry article

- Open Access

- Published:

Appraisal of systematic reviews on interventions for postpartum depression: systematic review

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 21, Article number:18 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Postpartum low (PPD) is a highly prevalent mental health problem that affects parental health with implications for child health in infancy, childhood, boyhood and beyond. The primary aim of this study was to critically appraise bachelor systematic reviews describing interventions for PPD. The secondary aim was to evaluate the methodological quality of the included systematic reviews and their conclusions.

Methods

An electronic database search of MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from 2000 to 2020 was conducted to place systematic reviews that examined an intervention for PPD. A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews was utilized to independently score each included systematic review which was then critically appraised to meliorate define the most effective therapeutic options for PPD.

Results

Of the 842 studies identified, 83 met the a priori criteria for inclusion. Based on the systematic reviews with the highest methodological quality, we found that employ of antidepressants and telemedicine were the almost effective treatments for PPD. Symptoms of PPD were as well improved by traditional herbal medicine and aromatherapy. Current evidence for physical practice and cerebral behavioural therapy in treating PPD remains equivocal. A significant, only weak relationship between AMSTAR score and journal impact factor was observed (p = 0.03, r = 0.24; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.43) whilst no relationship was found betwixt the number of total citations (p = 0.27, r = 0.12; 95% CI, − 0.09 to 0.34), or source of funding (p = 0.19).

Decision

Overall the systematic reviews on interventions for PPD are of low-moderate quality and are not improving over time. Antidepressants and telemedicine were the most effective therapeutic interventions for PPD treatment.

Background

Childbirth (parturition) can cause significant change in a adult female's priorities, roles, and responsibilities. Though there are many concerns for the female parent after parturition, emergence of postpartum depression (PPD) and clinical management strategies remain an important unresolved issue [i]. PPD is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV and is an increasingly prevalent mental health problem that typically begins four to six weeks later parturition [two]. Mutual symptoms include slumber and appetite disturbance, diminished concentration, irritability, anxiety, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities, depressed mood and thoughts of suicide [3].

The prevalence of PPD differs significantly depending on the land and ranges from 1.9 to 82.1% with the highest reported prevalence appearing in the United States and the lowest in Germany [4]. The consequences of PPD on the child are not restricted to infancy, and can extend into toddlerhood, schoolhouse age, and even adolescence. PPD can lead to inadequate prenatal care, childhood noncompliance, anger and dysregulated attention, and lower cognitive operation [5]. Equally the window to treat PPD is time-sensitive, information technology is critical to ascertain the efficacy and safety of different therapeutic options. PPD is a complex disorder whose pathophysiology remains poorly divers with sub-optimal therapeutic options and an expanding literature. Numerous systematic reviews describing therapeutic interventions for the management of PPD have emerged in the literature in recent years; however, the most effective therapeutic options remain poorly divers.

Evidence-based medicine is defined as using highest-quality show to inform clinical controlling [six]. In the hierarchy of testify, systematic reviews and meta-analyses sit as the very top [seven]. If done correctly, systematic reviews and meta-analyses are able to consolidate and summarize master evidence for clinicians and policymakers. Even so, when systematic reviews are poorly conducted, their risk to bias increases and can generate invalid and unreliable results. Guidelines such as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology accept been adult to ensure consistency in the methodological synthesis of systematic reviews [8, 9]. In add-on to those, the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool was developed and is a validated tool [10, xi] to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews.

Methods

The aim of this study was to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews on the efficacy and safety of different PPD interventions using the AMSTAR tool and to evaluate dissimilar therapeutic strategies stratified past methodological quality. The secondary aim was to investigate whether different publication characteristics (e.g. number of citations, impact factor of the journal, year of publication, funding source) were associated with the methodological rigour of the systematic review. This systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines [8].

Search strategy

A comprehensive electronic database search, with a validated search strategy from a medical librarian, of Embase, MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews from inception until March fifth, 2020 was conducted. Search terms include depression, postpartum or postal service-partum, postnatal or post-natal, and systematic review (Appendix S1). The complete search strategy is available in the online supplement (Table S1).

Written report selection

Search results were uploaded into the Covidence software platform (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd). Indistinguishable articles were removed, and a two-staged independent screening procedure was used to identify studies for inclusion. Pilots were run for the initial stage of screening until review authors (Due east.H., Due south.F., S.L. and J.Due south.) reached a Cohen'due south kappa inter-rater reliability value of 0.viii [12]. Subsequently, reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. Eligible articles proceeded to full-text screening. Discrepancies during either stage of screening were resolved by discussion among the authorship squad until a consensus was reached. The inclusion criteria involved: (1) the systematic review must investigate the rubber and/or effectiveness of any intervention treating post-partum depression; (ii) self-identified as a systematic review in the championship or abstract; (3) the systematic review must review primary literature. The exclusion criteria involved: (1) outdated reviews where an updated version was accessible; (2) systematic reviews of other systematic reviews; (3) meta-analyses that did not include a systematic review; (four) non-intervention systematic reviews (eastward.g. preventative or screening tools); (5) reviews aiming to investigate the state of literature, where patient outcomes were not the primary interest; (6) non-English literature, and (7) conference abstracts.

Data extraction

Data was independently extracted by authors (E.H., S.F., Southward.L. and J.Due south.). Domains extracted included publication details such every bit: journal and affect gene (from Clarivate Analytics), yr of publication, funding source (eastward.g. philanthropic, government, industry, etc.), total citations (from Google Scholar), disharmonize of involvement statement (dichotomous), the corresponding author's country, and the intervention studied (east.chiliad. peer back up groups, antidepressants, cerebral behavioural therapy, etc.). Discrepancies were resolved past give-and-take and consensus among the authorship team. The list of excluded studies is available in the online supplement (Table S2).

Adventure of Bias assessment

Authors (E.H., Due south.F., Southward.50. and J.S.) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the studies using the AMSTAR quality cess tool. Scores were tabulated using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Wash.). Review authors selected either "yes," "not applicable," "no," or "can't answer" for each of AMSTAR criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the authorship squad. A betoken was awarded for each of the AMSTAR criteria that received a "yes." No points were given for "not applicative," "no," or "can't reply". Therefore, the highest full score possible was eleven.

Strategy for data synthesis

Tables generated using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Wash.) were used to summarize information. GraphPad Prism (version 7.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., USA) was used to statistically analyze information. Pairwise correlations (AMSTAR Score vs. Total Citations, AMSTAR Score vs. Bear upon Factor, AMSTAR Score vs. Publication Year) were evaluated using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). A two-tailed T-Test was used to evaluate potential differences in AMSTAR Score in terms of source of funding (Cochrane article vs. not-Cochrane article, government vs. institution etc.). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Included studies were stratified into low, moderate, and loftier methodological quality, as identified by an AMSTAR score of 1–5, half dozen–8, and ix–11, respectively (Table S3). Findings from included studies were and so narratively synthesized inside each stratum. Greater accent was placed on extensively researched interventions or reviews with greater methodological rigor.

Results

Report selection

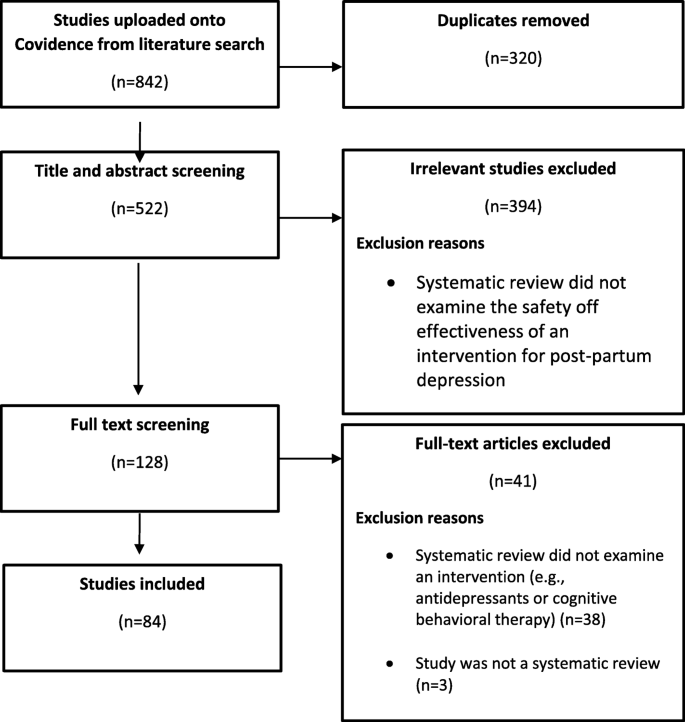

The electronic searches identified 842 publications, of which 320 (38%) were duplicates (Fig. ane). 522 articles proceeded to title/abstruse screening with 394 (47%) existence deemed ineligible every bit they did non evaluate an intervention for PPD. 128 (17%) full-text manufactures were retrieved and subjected to some other round of screening from which 41 (5%) studies were excluded as they did non examine interventions for PPD. Three (0.3%) more studies were excluded as they were not systematic reviews. Finally, 84 studies (10%) met the a priori inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included [thirteen,14,fifteen,16,17,eighteen,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,xl,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,lxxx,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95] for disquisitional appraisal.

Menstruation Diagram illustrating the management of article titles identified in our literature search, rationale for study exclusion and ultimate inclusion for critical appraisal

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of included studies are described in Table S1. The greatest number of studies (n = 15; 18%) were published in the Cochrane Library with the second most (n = 6; 7%) published in The Archives of Women'southward Health. Institutional funding involving hospitals and universities were involved with the largest proportion of studies (n = 28; 33%). Authorities sources of funding were involved in a minority of publications (due north = 17; xx%), no funding was reported for (n = xx; 24%) articles, and many articles failed to report a funding source (n = 25; 30%) (Table one).

Of the different therapeutic interventions described, peer support and grouping therapy were the intervention most frequently examined (n = 20; 24%), whereas cerebral behavioural therapy (CBT) and concrete activity were less frequently examined (northward = 17, 20%; n = x = 12%, respectively) of the studies reviewed. Some interesting interventions such every bit skin-to-peel baby contact, hypnosis, and specific traditional rituals were just reported in a single systematic review.

Methodological quality of included studies

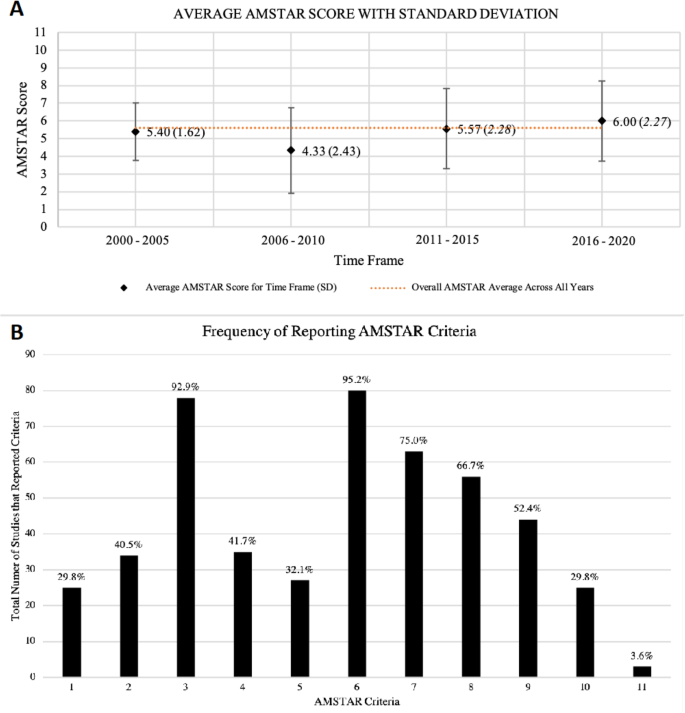

The overall AMSTAR score for included studies published from 2000 to 2020 had a hateful (SD) of 5.6 ± 1.half dozen (Fig. 2a). Compliance to each AMSTAR criteria was inconsistent across the studies (Fig. 2b). The overall methodological quality of the systematic reviews assessed was highly variable, with AMSTAR scores ranging from 1/11 (northward = 5; half dozen%) to x/11 (due north = ii; 2.iv%). The height three AMSTAR criteria that were nearly satisfied involved inclusion of the characteristics of included studies (criterion 6: n = 80; 95.ii% of studies), the performance of a comprehensive literature search (benchmark 3: n = 78; 92.nine% of studies), and the inclusion of a quality assessment (benchmark seven: north = 63; 75% of studies). The iii AMSTAR criteria that were the least frequently reported were the reporting of funding sources of included studies (criterion 11: n = 3; iii.6% of studies), and a tie between an a priori design and the cess for publication bias (criterion 1 and 10: n = 25; 29.viii% of studies), and the reporting of the included and excluded studies (criterion 5: northward = 27; 32.ane% of studies).

The Characteristics of the AMSTAR Assessment of Included Studies. A: The AMSTAR scores from 2000 to 2020, grouped into five-year intervals. Information represented as hateful (SD). The hateful AMSTAR score throughout the past twenty years was 5.6 (1.6). B: The number (%) of studies adhering to each AMSTAR criteria. Criteria: ane. Was an 'a priori' design provided? 2. Was in that location duplicate report selection and data extraction? 3. Was a comprehensive literature search performed? 4. Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion benchmark? 5. Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? half-dozen. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? 7. Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? 8. Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? 9. Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? 10. Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? 11. Was the conflict of interest included?

Synthesis of results

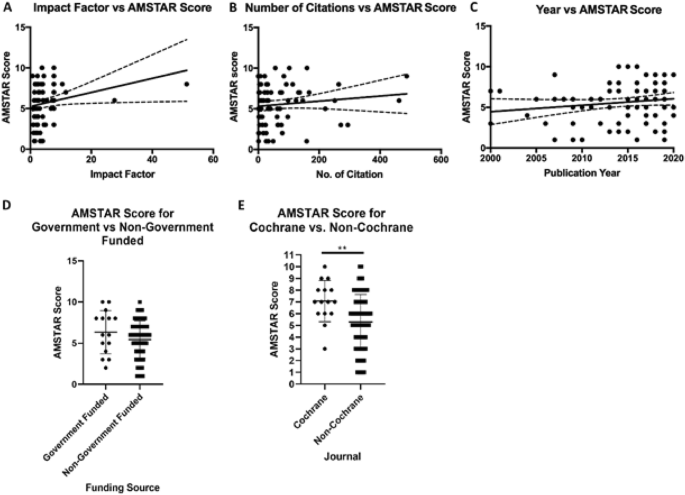

Almost one-half of the included systematic reviews were of depression quality (n = 37) as identified past an AMSTAR score of 1–5. A significant, simply weak relationship between AMSTAR score and periodical impact gene was observed (Fig. 3a; p = 0.03, r = 0.24; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.43). No significant relationships between mean AMSTAR score and number of citations (Fig. 3b; p = 0.27, r = 0.12; 95% CI, − 0.09 to 0.34) or publication year (Fig. 3c; p = 0.xiv, r = 0.16; 95% CI, − 0.05 to 0.37) were constitute. No pregnant differences (p = 0.19) were found between the AMSTAR scores of systematic reviews funded past authorities funding agencies, philanthropists, or institutions (Fig. 3d). On average, systematic reviews published by the Cochrane Collaboration scored higher than other published systematic reviews nosotros evaluated (p = 0.007) (Fig. 3e).

Association Betwixt Publication Factors and Methodological Quality. A: AMSTAR score vs. journal impact factor (p = 0.03, r = 0.24; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.43). B: AMSTAR score vs. number of citations (p = 0.27, r = 0.12; 95% CI, − 0.09 to 0.34). C: AMSTAR score vs. publication year (p = 0.14, r = 0.16; 95% CI, − 0.05 to 0.37). D: Differences in AMSTAR score in papers funded by government vs. non-regime sources. (p = 0.18) E: Differences in AMSTAR score for papers published by the Cochrane Collaboration vs. published in non-Cochrane journals (**p = 0.007)

For the most highly ranked systematic reviews, the most common interventions studied evaluated involved traditional interventions such as aromatherapy, acupuncture, and rituals [27, 85, 88, 89], as well equally more conventional therapies such as CBT [30, 39, 95], concrete activity [34, 65, 81], and pharmacological treatments [29, 42, 44, 55, 57, 79]. Positive benefits of aromatherapy on PPD were reported in two [85, 89] systematic reviews, but meta-analysis was non possible due to the heterogeneity of study designs therein. A systematic review on acupuncture reported a pooled mean difference of − i.27 (95% CI, − 2.55 to 0.01; p = 0.05, I2 = 83%) on the Hamilton Depression Scale between 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 887 participants [88]. However, they reported that the trials included therein had a high adventure of bias and that time to come trials with higher methodological rigour would be needed to ostend the benign effects of acupuncture. Finally, at that place was no articulate show on of a beneficial outcome of traditional rituals on PPD. [27]

The efficacy of cerebral behaviour therapy (CBT) as a PPD intervention was examined by multiple reviews. CBT reduced Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) low scores in a meta-analysis of six studies (− iv.48, 95% CI, 1.01 to 7.95) [xxx]. Some other meta-analysis of seven RCTs showed a significant size-outcome of CBT on reducing PPD (d = − 0.54, 95% CI, − 0.716; − 0.423) [95]. Nevertheless, a third systematic review found inconsistent and inconclusive results regarding its effectiveness [39]. Thus, the benefits of CBT every bit a therapeutic selection for the management of PPD remain to be antiseptic. It is important to note that main studies and trials with significant limitations were used to achieve these conclusions.

In the present review, near of the included systematic reviews were ranked as moderate quality (n = 39), characterized past an AMSTAR score of 6–eight. About a fourth of the studies in this stratum were published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (n = ten) and most of the reviews were either funded by institutions (n = 15) or did not receive fiscal support (northward = 12). The most extensively researched interventions in this stratum were also traditional interventions. Results of a meta-analysis of seven RCTs demonstrated that Chai Hu Shu Gan San had a greater effect on postpartum depression (mean departure = − 4.ten, 95% CI, − 7.48 to − 0.72, Iii = 86%) compared to fluoxetine [76]. Another systematic review also stated that other forms of Chinese herbal medicine could reduce low scores, lonely or in combination with routine treatments [53, 77]. Taken together these data suggest that traditional Chinese herbal medicine could accept beneficial effects in the handling of PPD and provide a useful alternative therapeutic option for women preferring natural therapies over conventional options.

Pharmacological interventions, including antidepressants and hormonal treatments, were besides extensively researched [1, 14, 43, 46, 87]. Estrogen therapy, progestin-only pills, and levonorgestrel intrauterine devices were reported to be effective, just a limited number of trials were referenced [87]. On the opposite, some other systematic review reported [24] that in a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial, norethisterone enanthate increased the risk of developing PPD (hateful EPDS score ten.6 vs 7.5; P = 0.0022). Three systematic reviews reported that fluoxetine [xiv, 43, 46] is an constructive therapeutic choice for PPD. Fluoxetine decreased EPDS depression scores from (9.9 (8.3 to 11.8)] to [7.3 (5.5 to nine.half dozen)) compared to placebo, in a trial with 87 women [14]. Information technology is reported that most included trials from these systematic reviews were indicated to have a high risk of bias and that results should be interpreted with caution [46].

The effectiveness of telephone back up equally a PPD intervention was investigated in 3 systematic reviews [22, 23, 37]. Findings of i report found that telephone support delivered past health professionals was associated with lower low scores in the postnatal period [37]. Telephone peer support was examined in a systematic review that included seven trials with 2492 participants. They found that telephone peer back up significantly reduced depressive symptomatology, as rated by the EPDS, at eight weeks postpartum (OR 6.23, 95% CI, i.40 to 27.84; P = 0.01) [22]. Nonetheless, the methods of administering peer telephone back up from the primary studies remain unclear. Additionally, evidence from another systematic review of five chief studies showed an average reduction in EPDS scores of 3.02 (95% CI, 5.34 to 0.70) [73]. Based on these systematic reviews with a off-white rating of methodological rigour, telecommunication strategies prove hope as an effective intervention for patients with PPD.

Physical practice was another extensively researched intervention. A systematic review conducted a robust variance estimation random-effects meta-analysis and plant a significant reduction in postpartum depression scores (Overall standard mean difference (SMD) = − 0.22 (95% CI, − 0.42 to − 0.01), p = 0.04; I2 = 86.iv%) in women physically active during pregnancy relative to those who were not [83]. Another systematic review constitute that exercise reduced women's PPD, equally reported past the EPDS, by − iv.00 points (95% CI, − seven.64 to − 0.35) [26]. These findings were contrary to a systematic review that did not find do to reduce postnatal depressive symptoms [68]. It is evident that studies with greater methodological rigour must be conducted to make up one's mind the effectiveness of physical exercise as an intervention for PPD.

The highest AMSTAR score accomplished was x/11 (due north = two) and involved a paper published in the Periodical of Epidemiology and Community Health, and another in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. One of these systematic reviews analyzed the apply of conventional pharmacological antidepressants [46], whereas some other examined the role of male involvement [52]. Important conclusions from these studies include that selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such equally sertraline, paroxetine and fluoxetine take been shown to have a positive bear on in mother'southward experiencing PPD (response: RR i.43, 95% CI, ane.01 to 2.03); remission: RR 1.79, 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.98). Furthermore, a conventional tricyclic antidepressant, nortriptyline, was as equally effective every bit sertraline. It was concluded that in that location was no meaningful deviation in agin effects between treatment arms in the studies included in the systematic reviews, although very limited information on effects experienced by breastfed infants were bachelor. Another written report [52] reported that male interest during antenatal care was associated with a greater utilization of healthcare services and higher quality postnatal care (OR = 1.35, 95% CI not reported; p = 0.01). Male involvement in the post-partum period significantly decreased the likelihood of PPD past 66% (OR 0.34, 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.62; Iii = 57%).

Word

Overall, our results revealed a depression-moderate level of methodological quality with no statistically significant changes in quality over the past 20 years. Use of antidepressants and telecommunications therapy were the most effective interventions for PPD based on the systematic reviews with the highest methodological quality. In addition, traditional Chinese herbal medicine was besides constitute to be an effective tool for the treatment of PPD and thus may serve every bit a useful treatment culling for women who adopt natural therapies over conventional methods. The use of physical exercise, hormonal therapies, and CBT for the treatment of PPD remain equivocal.

There was a weak but significant correlation observed betwixt AMSTAR score and the impact cistron of the journal, suggesting that leading journals may evaluate methodological quality a piffling more rigorously than others. Given the overall depression-moderate quality of systematic reviews, it would exist beneficial for editorial boards to integrate quality assessment tools in the peer review procedure. Furthermore, there was no meaning correlation between AMSTAR score and total number of citations an article had. This is an ascertainment that is consistently seen in other realms such as hematology [96].

Systematic reviews published by the Cochrane Library had an average score that was higher compared to non-Cochrane articles (p = 0.007). This observation supports the generally accustomed position that the Cochrane Collaboration sets a high standard for methodological rigour when undertaking systematic reviews. These results align with the findings from other medical disciplines regarding the methodological quality of Cochrane reviews equally well [97].

A big level of heterogeneity was observed in the quality assessment of peer-reviewed systematic reviews involving the safe and effectiveness of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions to treat PPD. AMSTAR scores ranged from 1/xi (n = five) to 10/eleven (north = two). The number of systematic reviews in this field has slowly increased over the past two decades, with the well-nigh (northward = 14) beingness published in 2019. However, our evaluation of systematic reviews (due north = 83) did not detect improvements in methodological rigour over the final 2 decades. This finding diverges from other areas in research, like radiology and critical intendance, in which methodological rigour of systematic reviews has improved over time [98, 99].

A strength of the present report is that a comprehensive literature search according to the AMSTAR criteria was conducted and the PRISMA statement was adhered to. A large scope of evidence was available and retrieved from the Cochrane Library, Medline, and Embase. One limitation of our report is that the quality of the systematic reviews evaluated was carried out by authors enlightened of the authorship and publication journal of the study. However, the potential for bias was reduced past several authors independently evaluating each systematic review, with final decisions for each quality assessment criteria followed by give-and-take until consensus was achieved. Furthermore, the analysis betwixt AMSTAR score and the number of citations may be affected by publication engagement of the systematic review. Recently published systematic reviews may not have garnered as many citations every bit older publications, fifty-fifty if AMSTAR scores may exist higher. Notwithstanding, nosotros utilized this metric equally it provides insight on how the methodological quality of given systematic reviews accept influenced the field.

Conclusions

The methodological rigor of the systematic reviews of therapeutic options for women with PPD over the past 20 years is of depression to moderate quality and has remained unchanged over time. We found that, based on the systematic reviews with the highest methodological quality, the utilize of antidepressants and telecommunication therapy are the most effective interventions for PPD. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine was effective in the direction of PPD and thus could provide a useful therapeutic alternative for women who prefer natural options over conventional therapies. The efficacy of physical exercise, hormonal therapies, and CBT for the handling of PPD remain equivocal.

Availability of data and materials

All information generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews

- CBT:

-

Cerebral behavioural therapy

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Low Scale

- PPD:

-

Post-partum depression

References

-

Cristescu T, Behrman S, Jones SV, Chouliaras L, Ebmeier KP. Be vigilant for perinatal mental health problems. Practitioner. 2015;259(1780):19–23 ii-3.

-

Nonnenmacher Due north, Noe D, Ehrenthal JC, Reck C. Postpartum bonding: the touch of maternal depression and adult attachment style. Curvation Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(5):927–35.

-

Norhayati MN, Hazlina NH, Asrenee AR, Emilin WM. Magnitude and adventure factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Bear upon Disord. 2015;175:34–52.

-

Montori VM, Saha S, Clarke Thousand. A call for systematic reviews. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1240–1.

-

Canadian Paediatric Social club. Maternal depression and child evolution. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9(eight):575–98.

-

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–2.

-

Petrisor B, Bhandari 1000. The hierarchy of prove: levels and grades of recommendation. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(1):11–five.

-

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health intendance interventions: caption and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

-

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-assay of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283(xv):2008–12.

-

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson East, Grimshaw J, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(x):1013–xx.

-

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers G, Andersson North, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;seven(1):10.

-

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(three):276–82.

-

Ray KL, Hodnett ED. Caregiver back up for postpartum depression. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000946.

-

Hoffbrand Due south, Howard Fifty, Crawley H. Antidepressant drug handling for postnatal depression. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2001;2:CD000946.

-

Levitt C, Shaw E, Wong Southward, Kaczorowski J, Springate R, Sellors J, et al. Systematic review of the literature on postpartum intendance: methodology and literature search results. Birth. 2004;31(3):196–202.

-

Lumley J, Austin MP, Mitchell C. Intervening to reduce depression later on nascency: a systematic review of the randomized trials. Int J Technol Appraise Health Care. 2004;xx(2):128–44.

-

Dennis CL. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal low: systematic review. Br Med J. 2005;331(7507):fifteen–eight.

-

Shaw E, Levitt C, Wong S, Kaczorowski J. Systematic review of the literature on postpartum intendance: effectiveness of postpartum support to ameliorate maternal parenting, mental health, quality of life, and physical health. Birth. 2006;33(iii):210–20.

-

Dennis CL, Hodnett ED. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD006116.

-

Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G. Postnatal depression: prevalence, Mothers' perspectives, and treatments. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(two):91–100.

-

Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Ross 50, Smith WCS, Helms PJ, Williams JHG. Effects of treating postnatal low on mother-infant interaction and child development: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(NOV):378–86.

-

Dale J, Caramlau IO, Lindenmeyer A, Williams SM. Peer support phone calls for improving health. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD006903.

-

Dennis CL, Kingston D. A systematic review of telephone support for women during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. JOGNN. 2008;37(iii):301–14.

-

Dennis CL, Ross LE, Herxheimer A. Oestrogens and progestins for preventing and treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD 001690. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001690.pub2.

-

Craig M, Howard L. Postnatal depression. BMJ Clin Evid. 2009;01:1407 PMID: 19445768.

-

Daley A, Jolly K, MacArthur C. The effectiveness of exercise in the management of post-natal depression: systematic review and meta-assay. Fam Pract. 2009;26(2):154–62.

-

Grigoriadis Southward, Robinson GE, Fung K, Ross LE, Chee C, Dennis CL, et al. Traditional postpartum practices and rituals: clinical implications. Tin can J Psychiatr. 2009;54(12):834–40.

-

Leis JA, Mendelson T, Tandon SD, Perry DF. A systematic review of home-based interventions to prevent and care for postpartum depression. Archiv Women Mental Health. 2009;12(1):3–thirteen.

-

Ng RC, Hirata CK, Yeung Westward, Haller East, Finley PR. Pharmacologic handling for postpartum low: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;xxx(9):928–41.

-

Stevenson Doctor, Scope A, Sutcliffe PA, Booth A, Slade P, Parry G, et al. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for postnatal low: a systematic review of clinical effectiveness, costeffectiveness and value of information analyses. Health Technol Assess. 2010;fourteen(44):1–152.

-

Goodman JH, Santangelo G. Group treatment for postpartum depression: a systematic review. Archiv Women Ment Health. 2011;14(iv):277–93.

-

Ni PK, Siew Lin SK. The part of family and friends in providing social back up towards enhancing the wellbeing of postpartum women: a comprehensive systematic review. JBI Lib Syst Rev. 2011;ix(10):313–70.

-

Dodd JM, Crowther CA. Specialised antenatal clinics for women with a multiple pregnancy for improving maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;eight:CD005300.

-

Nascimento SL, Surita FG, Cecatti JG. Concrete exercise during pregnancy: a systematic review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24(6):387–94.

-

Sado G, Ota E, Stickley A, Mori R. Hypnosis during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(vi):CD009062. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009062.pub2.

-

Scope A, Booth A, Sutcliffe P. Women'due south perceptions and experiences of group cognitive behaviour therapy and other group interventions for postnatal depression: a qualitative synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(9):1909–19.

-

Lavender T, Richens Y, Milan SJ, Smyth RMD, Dowswell T. Phone back up for women during pregnancy and the first six weeks postpartum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD009338. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009338.pub2.

-

Miller BJ, Murray L, Beckmann MM, Kent T, Macfarlane B. Dietary supplements for preventing postnatal low. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD009104. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009104.pub2.

-

Perveen T, Mahmood S, Gosadi I, Mehraj J, Sheikh SS. Long term effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for treatment of postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pakistan Med Stud. 2013;three(4):198–204.

-

Rahman A, Fisher J, Bower P, Luchters Due south, Tran T, Yasamy Yard, et al. Interventions for common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(8):593–601.

-

Scope A, Leaviss J, Kaltenthaler E, Parry G, Sutcliffe P, Bradburn M, et al. Is group cognitive behaviour therapy for postnatal low evidence-based exercise? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:321. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-321.

-

Sharma V, Sommerdyk C. Are antidepressants effective in the treatment of postpartum depression? A systematic review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;fifteen(6):PCC.13r01529. https://doi.org/x.4088/pcc.13r01529.

-

De Crescenzo F, Perelli F, Armando M, Vicari Southward. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for post-partum depression (PPD): A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Impact Disorder. 2014;152–154(one):39–44.

-

McDonagh MS, Matthews A, Phillipi C, Romm J, Peterson One thousand, Thakurta Due south, et al. Low drug handling outcomes in pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):526–34.

-

Miniati M, Callari A, Calugi Southward, Rucci P, Savino M, Mauri M, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a systematic review. Archiv Women Ment Health. 2014;17(iv):257–68.

-

Molyneaux East, Howard LM, McGeown HR, Karia AM, Trevillion Thousand. Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(9):CD002018. https://doi.org/ten.1002/14651858.CD002018.pub2.

-

Dodd JM, Dowswell T, Crowther CA. Specialised antenatal clinics for women with a multiple pregnancy for improving maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD005300.

-

Gilinsky Equally, Dale H, Robinson C, Hughes AR, McInnes R, Lavallee D. Efficacy of concrete activity interventions in mail-natal populations: systematic review, meta-assay and content coding of behaviour modify techniques. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;ix(2):244–63.

-

Gressier F, Rotenberg S, Cazas O, Hardy P. Postpartum electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review and case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(4):310–4.

-

Perry Thousand, Becerra F, Kavanagh J, Serre A, Vargas E, Becerril V. Community-based interventions for improving maternal wellness and for reducing maternal health inequalities in loftier-income countries: a systematic map of inquiry. Glob Wellness. 2015;10(1):63.

-

Tsivos ZL, Calam R, Sanders MR, Wittkowski A. Interventions for postnatal low assessing the mother-infant relationship and child developmental outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Women's Health. 2015;7:429–47.

-

Yargawa J, Leonardi-Bee J. Male person interest and maternal wellness outcomes: systematic review and meta-assay. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(six):604–12.

-

Li Y, Chen Z, Yu N, Yao G, Che Y, Xi Y, Zhai S. Chinese Herbal Medicine for Postpartum Low: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:5284234.

-

Madden Thou, Middleton P, Cyna AM, Matthewson G, Jones L. Hypnosis for pain management during labour and childbirth. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2016;(v):CD009356.

-

Mah BL. Oxytocin, postnatal depression, and parenting: a systematic review. Harvard Rev of Psychiatry. 2016;24(1):1–13.

-

O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartumwomen evidence report and systematic review for the Usa preventive services job force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388–406.

-

Saccone G, Saccone I, Berghella Five. Omega-three long-concatenation polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish oil supplementation during pregnancy: which evidence? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(15):2389–97.

-

Stephens S, Ford E, Paudyal P, Smith H. Effectiveness of psychological interventions for postnatal depression in primary intendance: a meta-assay. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(5):463–72.

-

Dhillon A, Sparkes Due east, Duarte RV. Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2017;8(six):1421–37.

-

Dixon Southward, Dantas JA. Best practise for community-based management of postnatal low in developing countries: a systematic review. Health Intendance Women Int. 2017;38(2):118–43.

-

Hadfield H, Wittkowski A. Women'south experiences of seeking and receiving psychological and psychosocial interventions for postpartum depression: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative literature. J Midwifery Women Wellness. 2017;62(six):723–36.

-

Hsiang H, Karen MT, Joseph MC, Nahida A, Amritha B, Rachel K. Collaborative Care for Women with Depression: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(1):11–8.

-

Mendelson T, Cluxton-Keller F, Vullo GC, Tandon SD, Noazin S. NICU-based interventions to reduce maternal depressive and feet symptoms: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20161870.

-

Pritchett RV, Daley AJ, Jolly K. Does aerobic exercise reduce postpartum depressive symptoms?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(663):e684–e91.

-

Saligheh M, Hackett D, Boyce P, Cobley Due south. Can exercise or concrete activeness help improve postnatal depression and weight loss? A systematic review. Archiv Women Mental Health. 2017;twenty(5):595–611.

-

Suto M, Takehara Thousand, Yamane Y, Ota Due east. Furnishings of prenatal childbirth instruction for partners of meaning women on paternal postnatal mental health and couple human relationship: a systematic review. J Bear on Disord. 2017;210:115–21.

-

Yonemoto North, Dowswell T, Nagai S, Mori R. Schedules for home visits in the early postpartum flow. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2017;8(8):CD009326. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009326.pub3.

-

Davenport MH, McCurdy AP, Mottola MF, Skow RJ, Meah VL, Poitras VJ, et al. Bear upon of prenatal exercise on both prenatal and postnatal feet and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(21):1376–85.

-

Gurung B, Jackson LJ, Monahan M, Butterworth R, Roberts TE. Identifying and assessing the benefits of interventions for postnatal depression: a systematic review of economic evaluations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):179.

-

Huang Fifty, Zhao Y, Qiang C, Fan B. Is cerebral behavioral therapy a better selection for women with postnatal depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Ane. 2018;13(10):e0205243.

-

Li South, Zhong W, Peng W, Jiang M. Effectiveness of acupuncture in postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupuncture Med. 2018;36(5):295–301.

-

Middleton P, Gomersall JC, Gould JF, Shepherd East, Olsen SF, Makrides M. Omega-3 fatty acid add-on during pregnancy. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2018;11(100909747):CD003402.

-

Nair U, Armfield NR, Chatfield MD, Edirippulige S. The effectiveness of telemedicine interventions to accost maternal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(x):639–50.

-

Owais S, Chow CHT, Furtado M, Frey BN, Van Lieshout RJ. Non-pharmacological interventions for improving postpartum maternal sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Slumber Med Rev. 2018;41:87–100.

-

Sikorski C, Van Hees S, Lakhanpaul M, Benton L, Martin J, Costello A, et al. Could postnatal Women'south groups be used to improve outcomes for mothers and children in high-income countries? A systematic review. Matern Child Wellness J. 2018;22(12):1698–712.

-

Sun Y, Xu 10, Zhang J, Chen Y. Treatment of depression with chai Hu Shu Gan san: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;eighteen(i):66.

-

Yang L, Di YM, Shergis JL, Li Y, Zhang AL, Lu C, Guo Ten, Xue CC. A systematic review of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine for postpartum depression. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:85–92.

-

Carter T, Bastounis A, Guo B, Jane MC. The effectiveness of exercise-based interventions for preventing or treating postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archiv Women Mental Health. 2019;22(one):37–53.

-

De Cagna F, Fusar-Poli L, Damiani S, Rocchetti M, Giovanna K, Mori A, et al. The role of intranasal oxytocin in anxiety and depressive disorders: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Euro Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(Supplement i):S498.

-

Ganho-Avila A, Poleszczyk A, Mohamed MMA, Osorio A. Efficacy of rTMS in decreasing postnatal depression symptoms: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:315–22.

-

Kolomanska-Bogucka D, Mazur-Bialy AI. Physical activity and the occurrence of postnatal depression-a systematic review. Medicina. 2019;55(ix):560 doi: 10.3390%2Fmedicina55090560.

-

Li Westward, Yin P, Lao 50, Xu S. Effectiveness of acupuncture used for the Management of Postpartum Depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:6597503. https://doi.org/ten.1155/2019/6597503.

-

Nakamura A, van der Waerden J, Melchior Yard, Bolze C, El-Khoury F, Pryor L. Physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum low: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:29–41.

-

Park Southward, Kim J, Oh J, Ahn S. Furnishings of psychoeducation on the mental health and relationships of pregnant couples: a systemic review and meta-assay. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;104:103439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103439.

-

Rezaie-Keikhaie Thou, Hastings-Tolsma M, Bouya S, Shad FS, Sari K, Shoorvazi M, Barani ZY, Balouchi A. Effect of aromatherapy on mail service-partum complications: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:290–v.

-

Scime NV, Gavarkovs AG, Chaput KH. The effect of pare-to-skin care on postpartum depression among mothers of preterm or depression birthweight infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:376–84.

-

Ti A, Curtis KM. Postpartum hormonal contraception use and incidence of postpartum depression: a systematic review. Eur J Contraception Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(2):109–16.

-

Tong P, Dong LP, Yang Y, Shi YH, Lord's day T, Bo P. Traditional Chinese acupuncture and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2019;82(9):719–26.

-

Tsai SS, Wang HH, Chou FH. The effects of aromatherapy on postpartum women: a systematic review. J Nurs Res. 2020;28(3):e96. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000331.

-

Westerhoff B, Trosken A, Renneberg B. Near:blank? Online Interventions for Postpartum Depression. Verhaltenstherapie. 2019;29(4):254–64.

-

Wilson Due north, Lee JJ, Bei B. Postpartum fatigue and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bear on Disord. 2019;246:224–33.

-

Yang W-J, Bai Y-M, Qin L, Xu Ten-50, Bao Thousand-F, Xiao J-L, et al. The effectiveness of music therapy for postpartum low: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;37(101225531):93–101.

-

Dol J, Richardson B, Murphy GT, Aston M, McMillan D, Campbell-Yeo M. Impact of mobile health interventions during the perinatal period on maternal psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review. JBI Database Arrangement Rev Implement Rep. 2020;18(i):30–55.

-

Huang R, Yang D, Lei B, Yan C, Tian Y, Huang X, et al. The short- and long-term effectiveness of mother-infant psychotherapy on postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Touch Disord. 2020;260:670–9.

-

Roman Yard, Constantin T, Bostan CM. The efficiency of online cognitive-behavioral therapy for postpartum depressive symptomatology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Women Health. 2020;60(1):99–112.

-

Eshaghpour A, Li A, Javidan AP, Chen Northward, Yang Due south, Crowther MA. Evaluating the quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses published on directly oral anticoagulants in the past v years. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020:bmjebm-2019–111326. https://doi.org/ten.1136/bmjebm-2019-111326.

-

Campbell JM, Kavanagh Southward, Kurmis R, Munn Z. Systematic reviews in burns care: poor quality and getting worse. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38(ii):e552–e67.

-

Delaney A, Bagshaw SM, Ferland A, Laupland K, Manns B, Doig C. The quality of reports of critical care meta-analyses in the Cochrane database of systematic reviews: an contained appraisal. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):589–94.

-

Tunis Equally, McInnes Medico, Hanna R, Esmail K. Clan of study quality with completeness of reporting: have completeness of reporting and quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in major radiology journals changed since publication of the PRISMA statement? Radiology. 2013;269(2):413–26.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros appreciate and wish to thank Ms. Denise Smith, Kinesthesia of Health Sciences, McMaster University, for her guidance in preparing the search strategy.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

RC: conceptualization, methodology, formal assay, writing – original draft and editing, visualization, projection administration. EH: investigation, writing – original draft. AL: methodology, formal assay, visualization. SL: investigation. SF: investigation. JS: investigation. WF: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft and editing, supervision, projection assistants. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Respective author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approving and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Table S1: Included Studies and Their Characteristics. Table S2: List of Excluded Studies and Their Reasons. Table S3: AMSTAR Scoring of Included Studies. Appendix S1: Search Keywords and Search Strings.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party cloth in this article are included in the article'south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the commodity'south Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, y'all volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chow, R., Huang, E., Li, A. et al. Appraisement of systematic reviews on interventions for postpartum depression: systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 18 (2021). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12884-020-03496-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03496-v

Keywords

- AMSTAR

- Cochrane reviews

- Methodological rigor

- PRISMA

- Mental health

- women'south health

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-03496-5